Somewhere in Podcastistan, I recently heard Harvard anthropologist Daniel Leiberman talking about how odd it is that humans exercise — of our own volition.

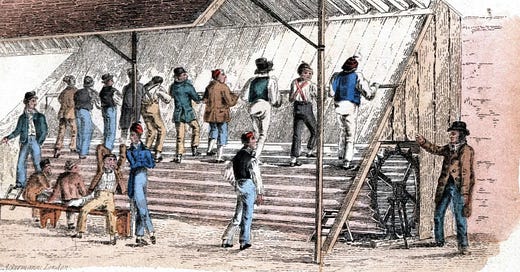

As someone who exercises a lot, arguably too much, this comment motivated a hard look in the mirror. Why on earth would anyone run, or ride a bike, or swim? Why would we drive to a gym to run in place on something originally conceived as a Victorian device of torture? Lifting weights makes perhaps the least sense of all. We load up bars with hunks of iron and then move them a few inches, often in really weird ways.

If you exercise, why do you do it?

Perhaps it’s to relieve stress, to help you focus, to control your weight, to look a certain way. Or maybe your doctor told you you needed to. Maybe it’s your primary social outlet. Maybe you even enjoy how it makes you feel, intrinsically, without anything more to it. Whatever the reason, take a moment to go one step deeper with that “why” question.

Where does that inquiry take you?

Exercise takes time and energy — scarce resources we presumably need to survive, or advance in our careers, be better parents, friends, spouses, whatever. Maybe we compete at something that requires fitness, but vanishingly few of us do that professionally. We used to exercise as part of our efforts to survive — hunting and gathering were great ways to get in our daily 10,000 steps. Finding or building shelter involved lifting heavy things. Avoiding predators made for great HIIT workouts.

Now, without exercise our physical and mental health deteriorate. What a curious paradox. We’ve innovated our way out of needing exercise to survive only to find that we need to exercise to survive. Technology generally makes things easier and more efficient, freeing up time and energy for supposedly higher order activities. That progression seems to function reasonably well for work — greedy jobs and their associated injustices aside — but it doesn’t do much for our bodies and minds.

So we do some rather silly things, often quite religiously. I dedicate hours and hours of my life to running and riding and skiing and lifting weights. Not only that, it’s a central component of my identity and value system, for better and worse. I attach virtue to exercise and judge others who don’t. That doesn’t seem good.

Why do I do it? I guess there are two categories of answers for me.

First, I do it to feel alive. I like fresh air, I like breathing hard, I like struggling and building toward some objective. I like the way I feel after — satisfied, somewhat proud, refreshed with more clarity. I really don’t enjoy manual labor, but I like knowing that my body can handle it if it needs to. I like imagining that if some natural disaster strikes and I need to grab a few things and run to safety, I can do it.

The other category includes things I’m less proud of. These center on image and identity. I like thinking I’m the sort of person who exercises a lot. Fitness offers me some level of distinction that feeds my ego. I was a chubby kid — something I grew out of for some constellation of reasons, most of which were likely outside of my control — and “overcoming” my adolescent body is an origin myth I draw strength and confidence from.

For many years I developed and justified my obsession with exercise and fitness through competition — high school and collegiate athletics, then bike racing, triathlons, ultramarathons. I no longer compete and the demands of work and family continue to increase, so this exercise paradox is coming into sharper focus.

It’s a colossal waste of time and energy. Yet it’s been central to many of the things I’m most proud of and the substrate for my deepest relationships. It reminds me I can do hard things and that hard things are worth doing. Resolving paradoxes can be a fool’s errand, and living right at the center of paradox is often the richest place to be, regardless of how absurd it is.